Why, What, How to Interpret Machine Learning Models in Medical Research

What are your feelings on AI (Artificial Intelligence) and ML (Machine Learning)? Are you excited, like waiting for a new video game or the latest iPhone release? Or are you fearful or concerned? If it’s the latter, what exactly worries you? Specifically, if you work in biology, bioinformatics, health informatics, or medical research, what aspects of AI/ML are most concerning? Perhaps it is because AI/ML applications in these fields feel more impactful than in others, as the decision can be life-changing. You might worry about losing your job, fearing that you can not compete with machines. Or you may be concerned about not being able to detect incorrect results produced by automated systems. You could also be experiencing the “Uncanny Valley” phenomenon in AI: people generally like human-like systems at first, but once they become almost human, the comfort levels drop sharply, leaving people uneasy or even repulsed.

However, we cannot avoid AI/ML simply because we are afraid or feel uncomfortable with it. Instead, we should dive deeper into this “magical” field, learn to understand it well enough to overcome our fears, and challenge any incorrect assumptions. The most dangerous mistake is to trust a machine without truly understanding how it works. So, let’s begin by exploring how these systems function, especially in the context of medical research.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a broad concept referring to any computer system designed to simulate human intelligence. In medical research, AI can include clinical decision support tools, automated diagnostic systems, or technologies that read and process medical records. Machine Learning (ML) is a subset of AI that focuses on learning patterns from data without relying on hand-crafted rules or explicit programming. ML is used in medical research to predict or diagnose disease risk from patient data, detect diseases from medical images, and identify biomarkers from genomic data.

Roles of ML in Medical Research

In this article, I will focus on machine learning (ML) in medical research, as artificial intelligence (AI) is broader and is outside my area of expertise. So, what is ML in general? ML is the process of discovering patterns in data to derive rules that can be applied to new datasets.

Imagine you want to predict whether a patient has cancer based on their symptoms, demographic information, and responses to a questionnaire, but without access to biopsy results for confirmation. The typical clinical process is to identify potential signs based on prior experience or medical knowledge, then proceed with further testing such as blood work, ultrasound, and eventually, biopsy. As you can imagine, this process requires a significant amount of time and relies heavily on the doctor’s careful examination and decision-making.

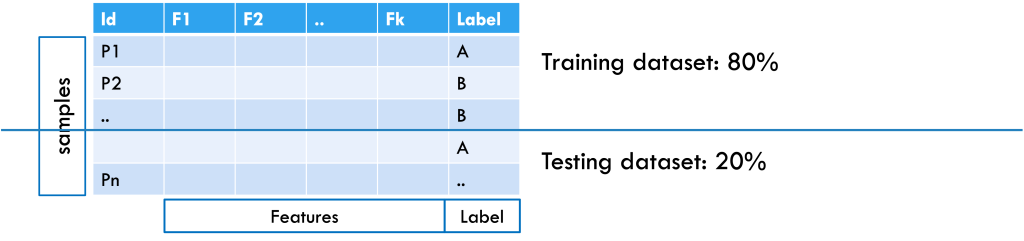

Here’s the process and role of ML in this decision-making context: First, data are collected from people who have already been diagnosed with cancer by doctors, as well as from people who are healthy or have other conditions. Each person is considered a sample, and each piece of information collected, such as age, blood test results, or scan findings, is called a feature. The dataset also includes whether each person has cancer or not, which serves as the label or output, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Example of a patient dataset formatted for machine learning, with an 80% training and 20% testing split. Samples are arranged in rows, features in columns, and the class label is included.

After collecting the data, it is split into training and testing sets (for example, 80% and 20%). The training set helps the machine learning system learn patterns in the features that separate cancer patients from non-cancer patients. If the dataset is large enough, the training set can be further split into a training subset (for learning the model) and a validation subset (for tuning hyperparameters and selecting the best model). To check how well the model works, it is tested on the testing set, where the labels are hidden. The model makes predictions based on what it learned, and these predictions are compared with the actual labels to measure accuracy. This approach considers all features together, since a single piece of information is usually not enough for a diagnosis. From the data, the model learns rules; for example, “A combination of elevated WBC, low platelets, and anemia suggests a 90% chance of cancer.” Once tested, the model can be applied to new patient samples to provide predictions.

Challenges in ML in medical research

What can go wrong? Well, every step can go wrong, and each step involves its own set of challenges. Applying ML to any research generally requires several key steps: defining a clear goal; collecting and preprocessing a dataset aligned with the goal; applying ML algorithms and evaluating them to select proper ones; and translating the results into a practical application. To illustrate these challenges, consider a case study to diagnose Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC), a rare and aggressive skin cancer [1]. Because MCC is difficult to diagnose early, even for experts, and its prognosis is equally challenging, researchers may turn to ML techniques to aid the diagnostic or prognostic process. This immediately raises a fundamental question: What kind of ML task is this?

Which ML task? Translating clinical questions into machine learning (ML) problems is not always straightforward. If your goal is early diagnosis of MCC, then it is a classification task, as you aim to classify cases as either MCC (positive class) or not (negative class). On the other hand, if your goal is to predict how much the tumor will grow over time to guide treatment decisions, that is, to prognose MCC, then it may be framed as a regression problem.

Additional complexity depends on the nature and availability of your dataset. If your data includes labeled examples (e.g., cancer vs. non-cancer for classification, or tumor size measurements over time for regression), then you are dealing with a supervised learning problem. However, if your dataset lacks labels, then it may fall under unsupervised learning.

ML-ready dataset Assuming a supervised classification task for early MCC diagnosis, the next challenge is assembling an ML-ready dataset. Ideally, this would include more than 1,000 complete and clean samples with balanced classes (MCC vs. non-MCC). In practice, MCC data rarely meet these conditions.

A key hurdle is defining the negative or control class. If controls are only healthy individuals, the model may simply learn “disease vs. no disease” instead of MCC-specific patterns. If controls are patients with non-cancer conditions, the task shifts to “cancer vs. non-cancer.” Including other skin cancers as controls creates a more targeted but difficult comparison. The choice of controls must therefore align with the project’s goal.

Data scarcity and inconsistency further complicate the problem. Since MCC is rare, data can be fragmented across institutions, and ethical or legal restrictions would limit access. Therefore, available datasets are typically small, imbalanced, and noisy, with inconsistent features due to varying diagnostic practices. Imbalance is particularly harmful: For instance, in a dataset of 500 samples (50 positives, 450 negatives), a split leaves only 10 positives in the test set. A model predicting all cases as negative would achieve 90% accuracy yet fail to detect any positives. This is the case where accuracy becomes misleading, and the dataset is unreliable for ML.

What is the ‘Right’ model? Some models are easy to understand, as they provide the rules in a human way. For example, Regression Models provide the model as a linear equation that adds each feature with their corresponding weight, and with a Decision Tree model, you can derive the rules that split to the next branch based on conditions and rules, and finally reach your decision. In those cases, the model itself can be interpretable, and you can evaluate the model with their domain contexts. Those interpretable ML models are referred to as White-box models [2]. However, they generally work well with certain assumptions, such as linear interactions of features, independence of features, or a small number of features. Therefore, in the process of data preprocessing, you could lose critical information or interfere with the interpretation of the predictions.

As ML develops, more computationally solid and complex models have been developed, including ensemble models, and it generally provides better results with standard evaluation metrics – e.g., accuracy, precision, or sensitivity. Since healthy and medical data are often longitudinal or irregular over time, in this case, you might need to use time-aware models, for example, RNNs, transformers, or survival models. However, those models are generally referred to as Black-box models, which hide the intrinsic structures and obstruct translating the results to their domain applications, leading to skepticism in the models.

Translating the results Now, with the trained model, you want to predict if a new patient will be correctly diagnosed with the disease by providing the patient’s information to the model. However, it just provides the predicted outcome with certain (e.g., 90%) accuracy. What if the outcome does not match your domain knowledge, or the outcome seems incorrect? You will ask “why?” with some following questions: Were the predictions made without bias?; are they reliable and safe? How were the predictions, and how does the model work?

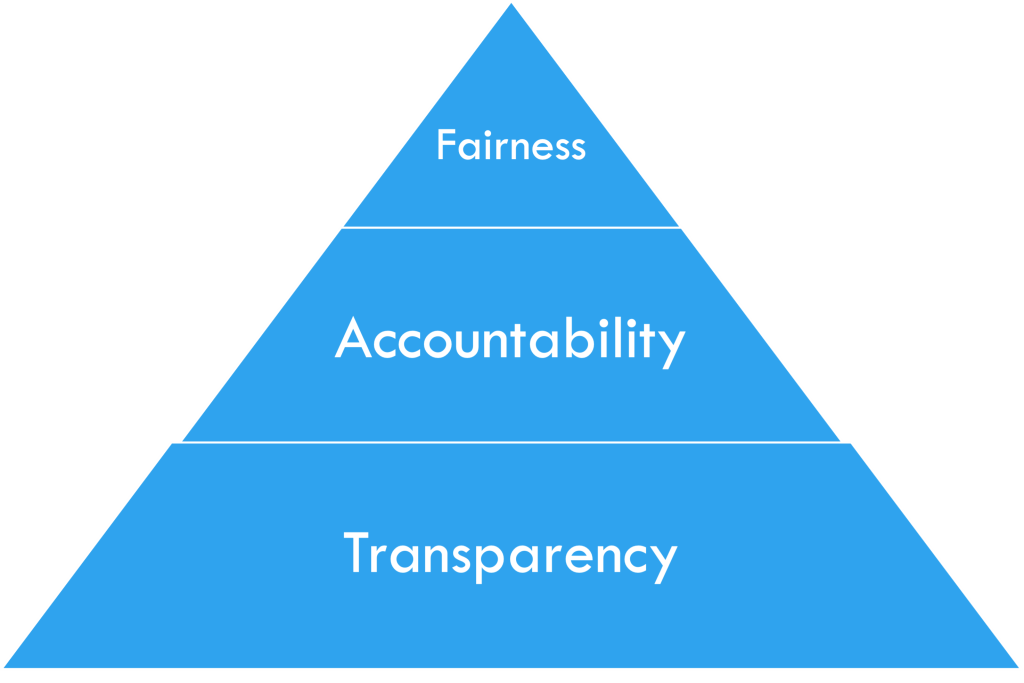

These questions lead to the main concepts of interpretable machine learning (iML), FAT: Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency.

Figure 2: FAT in iML, by courtesy of [2]

iML in medical research

Interpretable Machine Learning (iML) is a developing field that seeks to address the questions of Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAT) [2]. The FAT concepts are often organized in a pyramid form, as in Figure 2, with Fairness at the top and Transparency at the bottom, as each layer builds upon the previous one. In this section, I will discuss the ethical considerations of applying ML techniques to medical research and examine how they relate to each concept of FAT [3].

Fairness in medical research As a starting point in iML, the ethical consideration of fairness comes from the principle of Justice: Basically, it is asking whether the predictions are made without bias, and when applying ML in medical research, the following are the key fairness issues [4]:

- Representation bias: Is the dataset fair? Are certain subgroups (e.g., age, race, gender, or rare diseases) underrepresented?

- Labeling bias: Does the dataset include delayed or missed diagnoses? Are there misclassifications?

- Measurement or instrument bias: Do different labs use slightly different testing setups that could introduce variation?

- Evaluation bias: Are error rates equal across groups? Are evaluation metrics fairly applied and able to capture all necessary concerns?

Consider the MCC case as an example. It may show clear representation bias, since MCC cases are underrepresented. Some test results may be missing due to differences in insurance policies or patients’ financial constraints. Different practitioners may order different lab tests, further affecting representation. Labeling bias can occur when patients have different outcomes across timelines, as rare diseases often take time to be detected, and test results unrelated to MCC may look similar, which could add ambiguity. Measurement bias may arise from data collected across multiple hospitals with varying protocols. Finally, evaluation bias often follows from representation bias: if accuracy is used as the main metric, it may fail to capture the true detection rate for underrepresented classes.

Accountability in medical research Once fairness is addressed, accountability is grounded in the ethical principle of Responsibility: Who is responsible for errors or harm caused by ML predictions or the decisions informed by them? In iML, accountability highlights several key issues in medical research as follows [5, 6, 7]:

- Responsibility and liability: Who is accountable if harm occurs?

- Model reliability and safety: Does the model consistently provide the same outputs across populations or subgroups? Is its performance stable over time?

- Data quality and label integrity: Can we trust the model’s predictions if labels are temporally inconsistent? Is there data or target leakage, where a proxy for expert decisions unfairly influences model outcomes?

Consider the MCC case in terms of accountability. If the model misclassifies rare MCC cases, who should be blamed? Clinicians who used and trusted the system? ML developers who built it? Or data curators who prepared the dataset? Reliability may also be questioned if the model performs inconsistently across hospitals, especially when testing protocols differ. Another challenge is label integrity: MCC diagnoses can change over time, and models may suffer from target leakage, where certain features are influenced by expert curation rather than independent data.

Transparency in medical research Alongside fairness and accountability, transparency is tied to the ethical principle of Trust: Without sufficient transparency, trust in ML systems used in medicine can be compromised, and the key issues in transparency include the following [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13]:

- Model interpretability: Are the inner workings of the model understandable to clinicians, patients, and regulators? Can predictions be explained in a clinically meaningful way?

- Decision traceability: Can each prediction be traced back to the data and reasoning process that produced it? Is there an auditable record of model outputs?

- Communication of limitations: Are the model’s constraints, risks, and intended uses clearly communicated to all stakeholders? Are uncertainty estimates provided with predictions?

- Accessibility of information: Is sufficient documentation, such as data sources, pre-processing steps, and model validation results, made available for evaluation?

Consider the MCC case in terms of transparency. Since MCC is rare and often underrepresented, even a high-performing model may be opaque and difficult to interpret. Preprocessing steps can further obscure decision pathways, making it hard to trace why a prediction was made. Without clear communication between developers and clinicians about the model’s limitations and risk factors, it cannot be reliably adopted for life-critical decisions. Ultimately, transparency is essential to ensure safe and trustworthy access to information.

iML: Why, What, and How?

Why iML in medical research? Because machine learning (ML) alone is not sufficient in medical research, where decisions can be life-changing, iML is essential to ensure that models are both understandable and trustworthy. It is important to recognize that current iML techniques are limited in many ways and are mostly developed for general applications. Their direct use in medical and health research requires caution and, in some cases, the development of new domain-specific methods. Rather than focusing only on applying existing techniques, it is crucial to emphasize the underlying ethical principles of fairness, accountability, and transparency (FAT).

What is iML in medical research? Ideally, its focus is on interpretation without sacrificing performance. This allows it to reduce the risk of incorrect decisions, trace the reasoning behind decisions, and provide explanations for predictions in medical research. However, iML is still in its early stages, with few established standards, limited case studies, and only a handful of success stories in medicine. These factors make research on interpretable ML especially challenging, since interpretability must be demonstrated rather than assumed. Therefore, iML in medical research should include practical guidelines for use and proper evaluation metrics that measure not only performance but also

interpretability within the given context. Because decisions can be life-changing, iML in medical research is closely tied to ethics and regulations, requiring a broader and more practical understanding of interpretation.

Then how can iML be applied in medical research? First, current iML techniques can be leveraged, most of which help identify features that drive predictions. They can also generate counterfactuals that show what might change outcomes and provide human-readable rules to explain results. In our MCC case study, for example, the top-ranked feature might be a blood test or MRI result, which could serve as a valuable clinical guideline. At the individual patient level, counterfactuals can reveal what factors might have led to a different prediction, offering practical insights for prevention and early intervention. These functions embody fairness by clarifying which variables influence decisions, strengthen accountability by making model behavior examinable, and promote transparency by offering explanations in human-understandable terms.

Researchers must also be explicit about limitations and risks, supported by detailed documentation to ensure reproducibility and oversight. Since AI relies on vast and constantly evolving information sources, the reliability and timeliness of those sources are critical. Responsibility for trustworthy data extends beyond AI developers to the broader research community. Thus, monitoring, investigating, and developing better ways to maintain reliable data, while preventing the spread of misinformation, are also the researcher’s responsibility. Because outcomes directly affect human lives, especially in medical research, regulations guided by FAT principles should govern data collection, model use, and result interpretation from the outset. Without such safeguards, technological advances risk outpacing both ethical governance and clinical responsibility.

So, are you ready to bring AI and ML into your research?

References

- J. C. Becker, A. Stang, J. A. DeCaprio, L. Cerroni, C. Lebb´e, M. Veness, and

P. Nghiem, “Merkel cell carcinoma,” Nature Reviews Disease Primers, vol. 3, p. 17077, 2017.

- S. Mas´ıs, Interpretable machine learning with python. Packt Publishing Birming-ham, UK, 2021.

- T. L. Beauchamp and J. F. Childress, Principles of biomedical ethics. Edicoes Loyola, 1994.

- N. Mehrabi, F. Morstatter, N. Saxena, K. Lerman, and A. Galstyan, “A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning,” ACM computing surveys (CSUR), vol. 54, no. 6, pp. 1–35, 2021.

- D. S. Char, N. H. Shah, and D. Magnus, “Implementing machine learning in health care—addressing ethical challenges,” The New England journal of medicine, vol. 378, no. 11, p. 981, 2018.

T. Gebru, J. Morgenstern, B. Vecchione, J. W. Vaughan, H. Wallach, H. D. Iii, and K. Crawford, “Datasheets for datasets,” Communications of the ACM, vol. 64, no. 12, pp. 86–92, 2021.

H. Suresh and J. V. Guttag, “A framework for understanding unintended conse-quences of machine learning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.10002, vol. 2, no. 8, p. 73, 2019.

S. G. Finlayson, A. Subbaswamy, K. Singh, J. Bowers, A. Kupke, J. Zittrain, I. S. Kohane, and S. Saria, “The clinician and dataset shift in artificial intelligence,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 385, no. 3, pp. 283–286, 2021.

J. A. Kroll, “Accountable algorithms,” Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, 2015.

F. Doshi-Velez and B. Kim, “Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.08608, 2017.

C. Rudin, “Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes de-cisions and use interpretable models instead,” Nature machine intelligence, vol. 1, no. 5, pp. 206–215, 2019.

E. Begoli, T. Bhattacharya, and D. Kusnezov, “The need for uncertainty quantifi-cation in machine-assisted medical decision making,” Nature Machine Intelligence, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 20–23, 2019.

C. J. Kelly, A. Karthikesalingam, M. Suleyman, G. Corrado, and D. King, “Key challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence,” BMC medicine, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 195, 2019.

Subscribe Now to the Bio-Startup Standard

Notify me for the next issue!